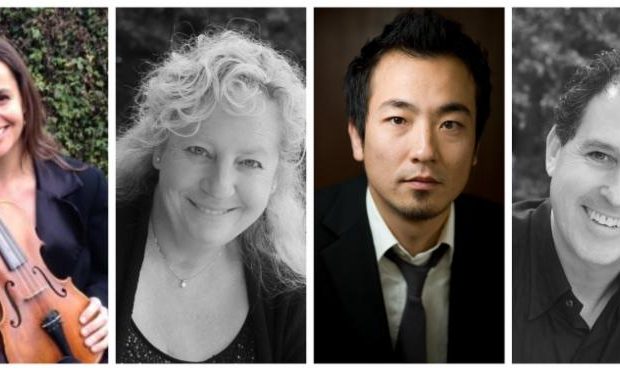

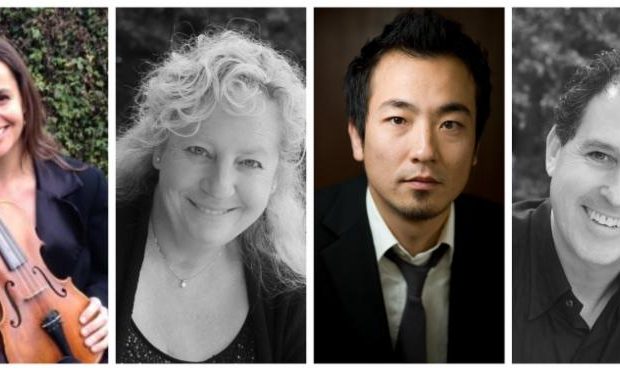

The concert on Oct. 13 by the Ives Collective brought together three imaginative chamber pieces and fabulous musicians from around the world. Japanese pianist Keisuke Nakagoshi and violinist Hrabba Atladottir, a native of Iceland who studied in Berlin, joined Artistic Directors Stephen Harrison and Susan Freier in an astonishing performance featuring works by Zoltán Kodály, Latvian composer Pēteris Vasks, and Erich Korngold.

Hrabba Atladottir

The concert at Old First Church began with Kodály’s charming Intermezzo for String Trio. Described by Harrison as a “palate cleanser” for the rest of the afternoon, the piece lasted no more than six minutes and was an enjoyable and fitting opening. Over a bed of lively pizzicato, it alternated sweeping melodies and harmonies possibly inspired by the folk music of Hungary. These gestures suggested much of the rest of the program, especially in its plucked accompaniment, melodies that grow out of a handful of notes, and inspiration from beyond the concert hall. Probably written around 1905, this was the oldest work on the program yet fit surprisingly well with Vasks’s Piano Quartet, written nearly a century later.

The Piano Quartet is comprised of six movements that emerge from stunningly simple piano chords, and the musicians seemingly created intensity out of nothing. The work layers and repeats material endlessly, then moves between its vastly different movements without pause to sustain its intensity. “Danze” featured a rhythmic dance that grows more anxious and frantic between its pizzicato and call-and-response sections, nearing a vigorous fever pitch before being rescued by the deep cello melody of “Canti drammatici” (Dramatic Songs). Its close intervals and unhurried pace were reminiscent of Gregorian chant, with something intensely primal about the sound emanating from Harrison’s cello that captured one’s soul. “Quasi una passacaglia” continued in earnest, with a nearly ominous low-bellied piano melody and whispering strings, contrasted by bringing the strings and piano to stratospheric heights. The energetic fervor of the passacaglia dissolved with another hauntingly beautiful song from the cello that was then passed up through the strings, reaching a wonderfully optimistic climax. The spell was finally suspended with the “Postludio,” which highlighted violinist Atladottir’s impeccable intonation and purity of tone.

Keisuke Nakagoshi

Clearly the focal point of the afternoon, Vasks’s Piano Quartet received a much-deserved standing ovation from the audience. The sincerity and emotion of the performers was evident and created an enchanting experience. If this was an audience member’s first listen — certainly possible, as the work was composed in 2001 and is relatively unknown — then it surely became an instant favorite.

The concert finished with Korngold’s Suite for Two Violins, Cello, and Piano Left Hand, Op. 23, composed in 1930. A fascinating composer perhaps best known for his film scores, Korngold’s expressiveness and clear sense of melody were on display here. Nakagoshi’s virtuosic performance of the opening cadenza gave the impression of two hands and immediately established his preeminent role within the piece. Afterward, the Suite moved seamlessly between energetic and insistent themes, a romantic waltz, childlike and carefree ditties, to a triumphant final proclamation. Effervescent violin lines from Atladottir and Freier further enhanced the performance. The effect was a luminous and intriguing performance by a very unique group.

The Ives Collective programmed a fascinating series of works and managed to connect them with their sensitivity and superb playing. Atladottir and Nakagoshi brought brilliant virtuosity to their performances, turning these chamber pieces into an enchanting and intimate afternoon.

Catriona Barr is a musicologist and music teacher based in San Francisco. She holds a B.M. from Peabody Conservatory and a M.M. from King’s College, London.